Discover the meaning and magic of abstract photography—from Schadographs and Rayographs to modern digital experiments. Learn why every photographer should explore abstraction and how it can clear your mind and fuel creativity.

Hello, fellow visual explorer! If you’ve ever found yourself captivated by the dance of light on a rainy window, or the cracked texture of an old wall, you’re already halfway into the world of abstract photography—even if you didn’t realize it.

Today, we’re diving into this beautiful, often-overlooked genre—not just to understand what it is, but to explore how it can deeply influence the way you see, shoot, and even feel as a photographer. By the end of this post, you won’t just understand abstract photography—you’ll want to grab your camera (or your phone), head out the door, and start bending reality yourself.

We’ll explore mind-bending tips to get you started, meet the legendary artists who made abstract photography what it is today, and even peek into a handful of must-read books that’ll spark your creative fire.

Let’s dive into the beautiful chaos!

The Meaning and Magic of Abstract Photography

Abstract photography borrows from that same principle: it’s not what you photograph—it’s how you photograph it.

You might be capturing the texture of rust, reflections on water, or a blur of color through a moving train window. The image may no longer be instantly “readable,” but it’s felt. It creates mood, stirs curiosity, and allows personal interpretation.

In an image-saturated world where everything looks similar, feels mainstream, and is definitively tagged, labeled, and decoded in milliseconds, abstract photography says – “Wait. Feel this.”

What Does “Abstract” Really Mean in Art?

Before we talk lenses and exposures, let’s talk essence.

In visual art, abstraction is the practice of stepping away from literal representation. Whether it’s a painting, a sculpture, or a photograph, abstract art focuses more on form, color, texture, pattern, light, and shadow—less on subject. It invites the viewer to engage emotionally or intellectually without the need for clarity or realism.

It’s not about depicting reality—it’s about expressing reality as felt, thought, or imagined.

Why You Must Explore Abstract Art & Photography

Even if your main genres are street, travel, or portrait photography, dabbling in abstraction isn’t just a side hobby—it’s a mental and creative recalibration.

Here’s why abstract art (including photography) is far more than just “art for art’s sake”.

Abstraction Trains You to See—Not Just Look

Conventionally, we often chase a subject—a face, a scene, a decisive moment. But abstract photography flips that and asks: “What if the subject is light itself? Or texture? Or motion? Or the absence of clarity?“

When you photograph something purely for their shapes, tones, and rhythms, your eye becomes sharper. You stop labeling things and start observing them. Suddenly, your backgrounds become richer, compositions tighter, colors more intentional.

It Stimulates Lateral, Intuitive Thinking

Abstraction activates the right side of the brain—the part that handles intuition, pattern recognition, and creative leaps.

It’s like cross-training for the creative mind. If documentary photography is a logical pursuit, abstraction is your creative yoga.

This is why many great photographers—Saul Leiter, Ernst Haas, Rinko Kawauchi—float freely between realism and abstraction. They treat the camera not just as a witness, but as a painter’s brush.

It Helps You Break Free from the Need to Explain

We live in a world obsessed with clarity and meaning. But not everything has to be ‘understood’—some things just need to be felt. Abstract art helps you:

- Embrace ambiguity.

- Let go of needing a story in every image.

- Accept beauty for beauty’s sake.

This mindset is invaluable for when your documentary work or portraiture needs more emotional texture and less exposition.

It’s Deeply Meditative and Helps You Declutter

Abstraction can be incredibly therapeutic. When you’re:

- Watching reflections ripple in a puddle

- Capturing motion blur from a passing crowd

- Zooming into color stains on a peeling wall…

You’re fully present. No judgment. No client brief. Just you and the frame.

It becomes a form of creative mindfulness—which helps you:

- Reconnect with the joy of image-making without pressure

- Detox from visual noise

- Listen to your core instincts

It Loosens You Up Creatively and Invites Play

Let’s be honest—every genre has its “rules.” Composition, lighting, subject hierarchy, etc.

Abstract photography invites rebellion.

You can:

- Tilt your camera at odd angles

- Drag the shutter

- Blur the whole frame

- Layer textures in post

- Shoot through rain-smeared glass

There’s a joy in that rebellion. And it’s liberating.

Often, when you return to your genre after a round of abstract experiments, your approach feels looser, more poetic, less formulaic.

It Sharpens Your Eye for Design & Composition

Abstract art relies heavily on:

- Lines

- Form

- Balance

- Negative space

- Color theory

These aren’t just abstract principles—they’re core visual tools. Mastering them through abstract experiments makes your work in fashion, architecture, product, or even street far more refined.

Think of it this way: abstract photography is a design gym for your vision.

It Reveals Your Inner Voice

Since abstraction has no literal subject, the only thing left in the frame is your eye.

- What you notice.

- What you value.

- What you’re drawn to.

It’s a mirror into your visual DNA—which becomes especially powerful in developing a personal style.

In short, even if you’re a genre-purist, abstract photography teaches you to see more deeply, shoot more intuitively, and connect more honestly. The idea is to tune into a different frequency of creativity. A purer one. A quieter one. A more personal one.

Practical Tips to Start Your Abstract Photography Journey

- Intentional Camera Movement

- Long Exposure + Minimalism

- Macro and Close-Up Abstraction

- Juxtaposition & Disorientation

Intentional Camera Movement (ICM)

What: Move the camera during a long exposure.

How: Use slower shutter speed and move the camera up/down, sideways, or in curves.

Pro Tip: Use slow dance-like motion for softer results, or jerky movement for chaotic energy.

Long Exposure + Minimalism

What: Use time to blur motion—waves, clouds, people.

How: Tripod + slow shutter speed (10–30 sec) + ND filter.

Pro Tip: Underexpose slightly for a moody feel.

Macro and Close-Up Abstraction

What: Shoot close to reveal textures/patterns/ details without context.

How: Use a macro lens or extension tubes.

Pro Tip: Convert to black-and-white to emphasize texture over subject.

Juxtaposition & Disorientation

What: Create visual tension by mixing elements or images.

How: Frame scenes with contrasting shapes, patterns, colors—or shoot reflections in puddles or mirrors.

Pro Tip: Rotate the image 90 degrees. Abstracts often come alive when flipped!

How I Create Abstract Work

When I set out to create abstract images, I’m often drawn to reflections, distorted shapes, intriguing textures, and rhythmic patterns. My compositions become more intimate and deliberate, as I aim to eliminate any obvious context or recognizable subject. I also explore abstraction through techniques like intentional camera movement and multiple exposures—allowing motion and layering to disrupt visual expectations. Even in post-processing, I enjoy playing with disorientation or crafting symmetry through duplication, pushing the image further into the realm of the abstract. See my work here

Timeline: The Trailblazers of Abstract Photography

Let’s take a short, inspiring walk through the timeline of abstract photography and the pioneers who expanded its language:

Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882–1966)

- Work: Vortographs (1916-17)

- Among the earliest abstract photographers, Coburn used a prism device called the “Vortoscope” to create kaleidoscopic compositions that looked nothing like traditional photos.

Paul Strand (1890–1976)

- Work: Porch Shadows (1916)

- Though best known for his documentary realism, Strand’s play with shadow and structure turned architectural spaces into abstract masterpieces.

Christian Schad (1894–1982)

- Work: Schadographs (1918–1919)

- His “Schadographs” were made by placing scraps like fabric, paper, and other materials on light-sensitive paper and exposing them to light—without a camera.

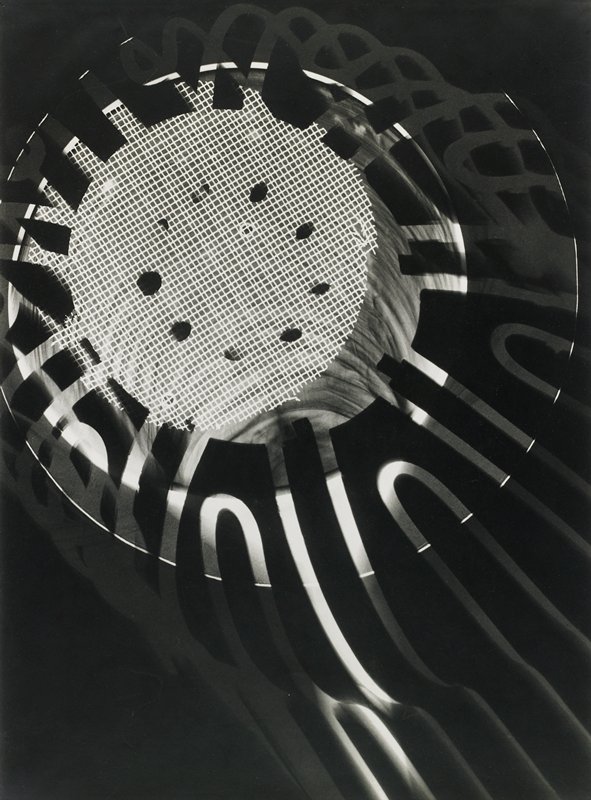

Man Ray (1890–1976)

- Work: Rayographs (1922)

- Deeply experimental, Man Ray used randomness, surrealism, and shadow-play to transform everyday objects into mysterious compositions.

Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946)

- Work: Equivalents series (1922–1934)

- Possibly the first intentional abstract photographic series—Stieglitz believed a photo could function like music or painting, conveying feeling without showing a specific subject.

László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946)

- Work: Photograms (1926)

- A Bauhaus legend, he pushed photography beyond the camera using cameraless methods. His photograms explored shadow, transparency, and light as building blocks of abstraction.

Aaron Siskind (1903-1991)

- Work: Jerome, Arizona (1949)

- Known for abstract images of peeling paint, graffiti, torn posters, cracked surfaces, etc. Treated these textures and forms as flat, expressive compositions, much like abstract paintings.

Carlotta Corpron (1901–1988)

- Work: Light Drawings

- Called the “Poet of Light,” she manipulated light and transparency to produce futuristic, delicate abstractions that were ahead of her time.

Minor White (1908–1976)

- Work: Moenkopi Strata, Capitol Reef, Utah (1962)

- For White, abstract photography was a form of meditation. His symbolic images invited the viewer to find emotional or spiritual parallels within.

Eiko Yamazawa (1899–1995)

- Work: What I Am Doing

- Later in her career, Yamazawa shifted from portraits to vivid, color-saturated abstractions that challenged gender norms and Japanese artistic traditions.

Barbara Kasten (b. 1936)

- Work: Construct series (1979 onwards)

- Uses mirrors, colored lights, Plexiglas, and sculptural setups to construct and photograph geometric scenes which often mimick the look of abstract painting or digital renderings.

James Welling (b. 1951)

- Work: Photograms, Glass House Series

- Welling uses unconventional materials and methods—like aluminum foil and colored gels—to create highly aesthetic, often disorienting abstractions.

Ellen Carey (b. 1952)

- Work: Pulls, Struck by Light

- Known for cameraless experiments and bold color interventions, Carey’s abstract images defy logic and lean into chance, emotion, and the unconscious.

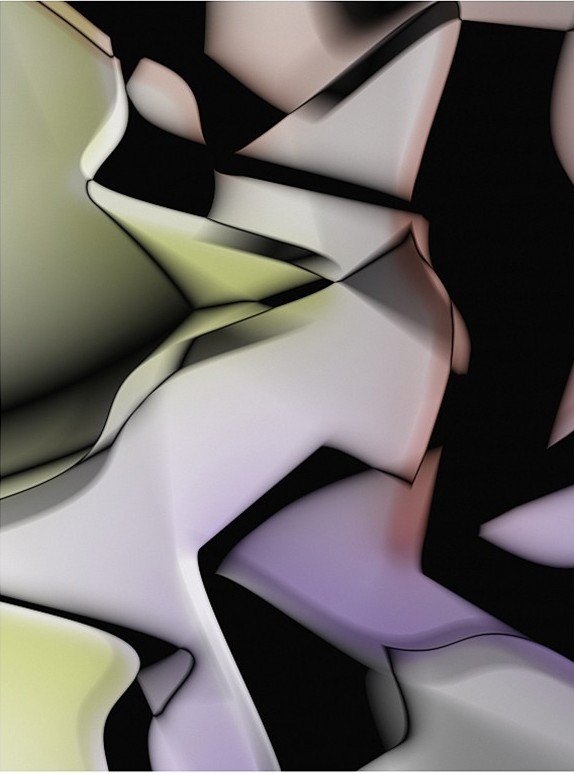

Thomas Ruff (b. 1958)

- Work: Substrate and jpeg series

- Ruff explores digital abstraction by manipulating low-resolution images and playing with compression artifacts—challenging our very perception of image clarity and meaning.

Wolfgang Tillmans (b. 1968)

- Work: Freischwimmer, Silver, Blushes

- Tillmans creates some of the most sensuous, large-scale abstract photographs today—many without a camera—by manipulating photographic paper and chemistry directly.

Walead Beshty (b. 1977)

- Work: Photograms from folded photo paper and airport x-rays, FedEx Works (2000)

- Famous for colorful photograms made by folding photo paper and exposing it to light or x-rays.

What is Vortograph?

A vortograph is a special kind of abstract photo that looks like a kaleidoscope image. It doesn’t show real things like people, places, or objects in a normal way. Instead, it shows patterns made of light, shapes, and reflections.

It was invented over 100 years ago by a photographer named Alvin Langdon Coburn.

To make a vortograph, he used three mirrors arranged in a triangle, placed in front of his camera lens. When he took a photo through those mirrors, it created a cool image full of repeating patterns, angles, and abstract shapes—kind of like what you see when you look through a kaleidoscope toy!

Read more here

What is Photograms?

A photogram is a photo made without a camera. You put objects like leaves or keys on special photo paper, shine light on them, then develop the paper.

Where the light hits the paper, it turns dark. Where the object blocks the light, it stays light—like a shadow picture!

Moholy-Nagy was an artist who made amazing abstract pictures using this method. He used glass, wire, and other objects to create cool, dreamy images—just by playing with light and shape.

What is Rayographs?

A Rayograph is a special kind of photogram—a photo made without a camera.

The artist Man Ray made them by placing random everyday objects (like pins, combs, or paper clips) on photo paper, then shining light on it. After developing the paper, the objects showed up as shadowy shapes!

He called them “Rayographs” after his own name—Man Ray—to make them unique.

Man Ray didn’t plan his Rayographs too much. He liked surprises and wanted to see what would happen. His art was fun, playful, and strange, using light and objects in a totally new way.

What is Schadograph?

Schadographs are a kind of picture made without using a camera. Christian Schad, a German artist, made them in the 1910s by placing things like pieces of paper, fabric, or string directly onto photo-sensitive paper (a special paper that reacts to light). Then he exposed it to light.

Where the objects blocked the light, the paper stayed white. Where the light hit the paper, it turned dark. After developing it, the result was a strange abstract image made up of shadows and shapes.

It’s like making a shadow collage with light—kind of like magic!

Final Words: Go Abstract, Go Deep

The best part of abstract photography? There are no rules—only discoveries.

You might find your style. You might not. But you’ll certainly see the world differently. You’ll see more. Feel more. And who knows—on days when the world feels too loud or too literal, this quiet practice might bring you back to yourself.

Now let’s enjoy the wild, weird, and wonderful world of abstract photography from these legendary artists. Who knows, you might just find some magic in the madness.

More Photographers to Explore: Karthik K Samprathi | Aaron Reed | Milan Radisics | Leah Freed

Alvin Langdon Coburn

László Moholy-Nagy

Alfred Stieglitz

Aaron Siskind

Must-Read Books on Abstract Photography & Art

This is the definitive book on abstract photography. It offers a chronological history of the genre, features stunning images, and provides critical essays on how abstraction evolved as a visual language in photography.

Covers artists like Alvin Langdon Coburn, Moholy-Nagy, Ellen Carey, and contemporary innovators.

Available on Amazon here

by Simon Baker

Available on Amazon here

A visually rich, deeply researched book from Tate that explores the conversation between photography and abstract painting over the past century.

Features pioneers like Moholy-Nagy, Paul Strand, Man Ray, and modern icons like Thomas Ruff and Wolfgang Tillmans.

Ideal for understanding the historical and artistic evolution of abstraction.

Other Books to Explore

László Moholy-Nagy: Painting After Photography” by Zsuzsanna Szegedy-Maszák

Focuses on Moholy-Nagy’s revolutionary use of light, shadow, and form in both painting and photograms.

Helps connect abstract photography with the Bauhaus movement and modern design.

A must-read if you’re curious about the origins of photograms and light-based abstraction.

Man Ray: Writings on Art

A rare, insightful collection of thoughts, experiments, and philosophy from Man Ray himself.

Helps you understand Rayographs and how abstraction can be playful, rebellious, and intuitive.

Perfect for artists who want to break rules and let go of control.

“James Welling: Monograph” edited by James Crump

A beautifully designed, in-depth book chronicling Welling’s diverse experiments with abstraction, light, materiality, and form.

Great for seeing how abstraction can evolve over a photographer’s lifetime.

Discover more from Creative Genes

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “Unlocking the Invisible: A Journey into Abstract Photography”